Disrespect and abuse in maternity care: individual consequences of structural violence

Tanzania has made slow progress in reducing maternal mortality, failing to achieve Millennium Development Goal 5.1 Significant progress between 1999 and 2015, however, was achieved in increasing facility births (from 47% to 63%).2While this is a reason for optimism, over recent years several studies have reported evidence that raises concerns about the poor quality of care women receive in some of these Tanzanian institutions, including frequent experiences of disrespectful and abusive treatment by health providers during childbirth.3–5

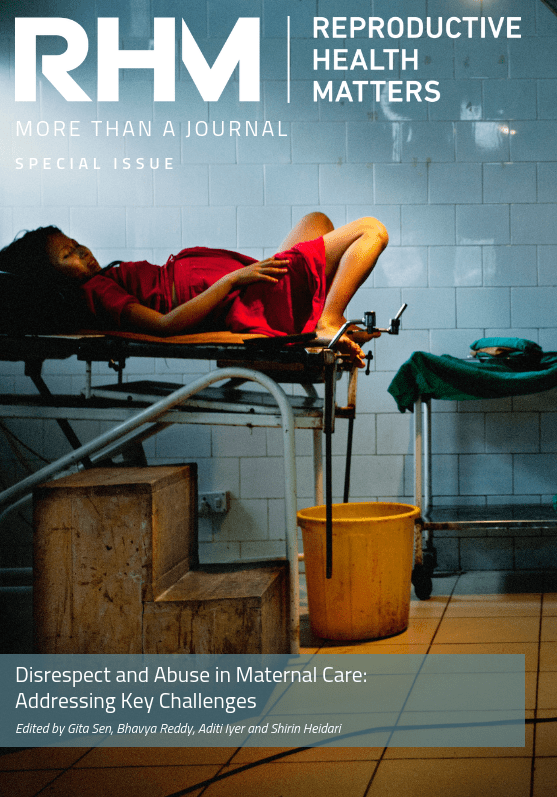

Disrespectful and abusive treatment during childbirth is a violation of women’s fundamental human rights, can negatively influence birth outcomes and discourages women from seeking future care.6Numerous individual practices and behaviours of health care providers can be considered as disrespectful and abusive, depending on the definitions that are used. Examples range from behaviour being non-supportive (such as not providing information) to physically harmful practices (such as slapping or beating).7

Mistreatment of women in health facilities is rooted in pervasive gender inequalities and power imbalance between health providers and women.8 Therefore, disrespect and abuse can be viewed as a consequence of structural violence.9 Structural violence refers to social forces that create and maintain inequalities within and between social groups, which make way for conditions where interpersonal maltreatment and violence may be enacted.11,12 Although the term “violence” speaks to the physical nature of disrespect and abuse in childbirth, the essence of structural violence lies in the indirect, systematic and often invisible infliction of harm on individuals by social forces that disable individuals from having their basic needs met.11We may be tempted to analyse this phenomenon in a narrower framework, such as seeing women as “victims” and health workers as “perpetrators” of abuse.13 However, the mistreatment of women in health facilities is systemic and requires a more structural analysis to look at the issue as a consequence of women’s lives not being valued by larger social, economic and political structures.14 ,15

Despite 30 years of action at the global level to improve care for women during pregnancy and birth, many countries, including Tanzania, have never been able to make the financial investments required.14 Instead, expenditures for maternal health over the past decades have increasingly relied on household contributions.1 In response to structural adjustment policies, the Tanzanian government introduced cost-sharing and decentralisation and reduced the already limited number of health workers and their salaries. Up until today, the human resource scarcity remains a major bottleneck.16 At the same time, the population has doubled, increasing the burden on a fragile health system. HIV/AIDS and more recently non-communicable diseases have contributed to this fragility.17 It is not surprising that increasing resource challenges and overload of health facilities have resulted in decreased health worker morale, lack of compassion, fatigue, and sometimes burnout, which are often reported to be underlying reasons for mistreatment of women.18

Over a decade ago it was suggested that ensuring respectful, high-quality care for all women was a matter of political will to value the lives of women and newborns.20 Nevertheless, the Safe Motherhood policy discourse remained focused on technical solutions and scaling up simple disease-specific interventions, particularly a focus on skilled birth attendance and access to emergency obstetric care.21–23 Simultaneously, health system challenges, including limited resources, insufficient training and poor working conditions of health providers, continued and/or deteriorated even further. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth occurs in an impoverished social and political context, in which women’s broader needs during pregnancy and birth have been systematically ignored or devalued. In this paper, we describe how and why women’s exposure to disrespect and abuse in health facilities should be seen as symptomatic of structural violence.

Read “Disrespect and abuse in maternity care: individual consequences of structural violence”.

Corporate Author: Andrea Solnes Miltenburg, Sandra van Pelt, Tarek Meguid & Johanne Sundby

Source: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09688080.2018.1502023