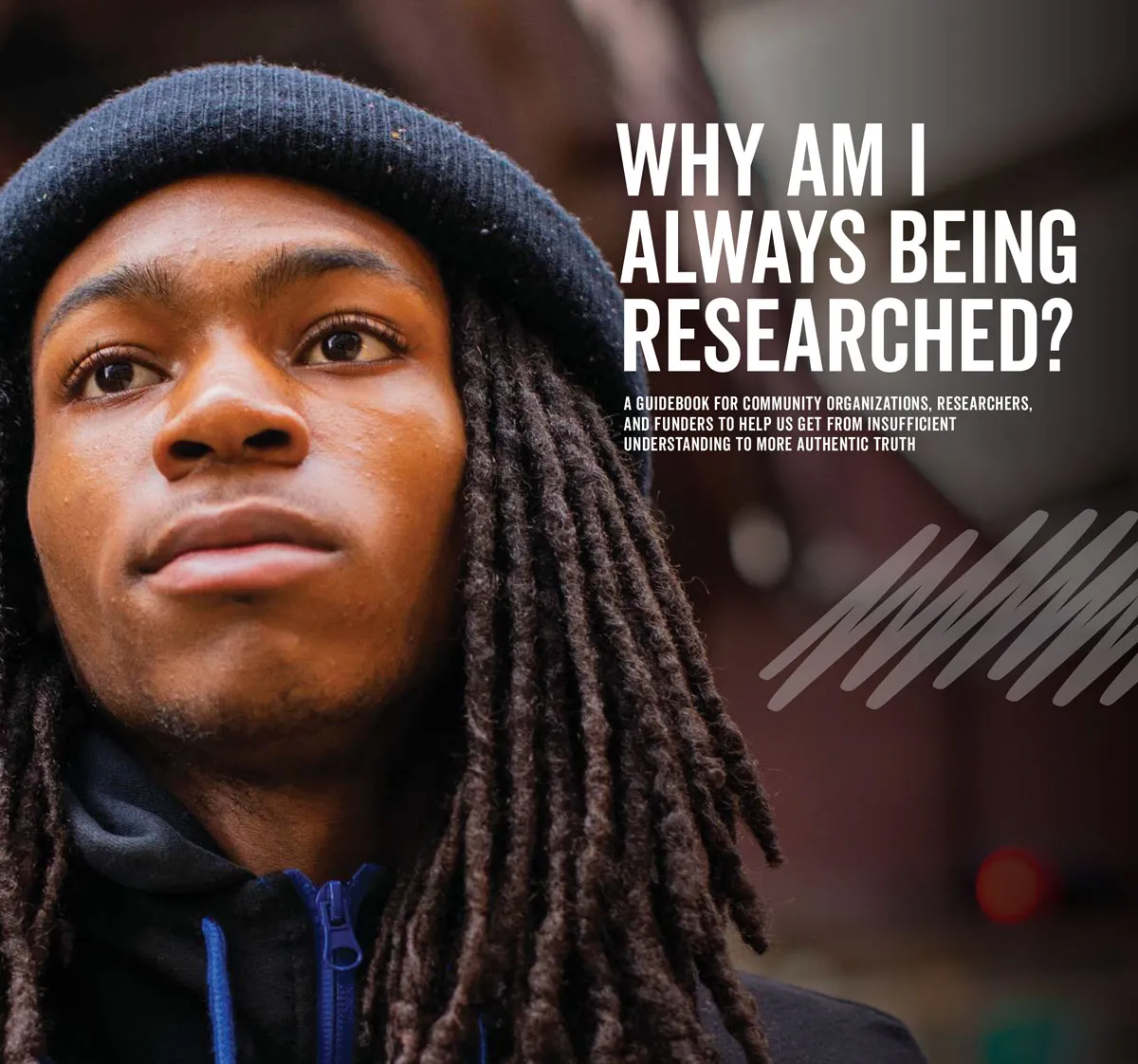

Why Am I Always Being Researched?

“Those involved in research design must recognise unintended bias to arrive at an authentic trust that does the most good for those being researched.”

This guidance from Chicago Beyond is a MUST-READ for community organisers, researchers, and funders. The guidance highlights seven inequalities in research that are reinforced by power dynamics. Here are some of questions researchers, funders, and community organisers can reflect on before conducting research:

🚩 Access: Could we be missing out on community wisdom because conversations about research are happening without the community meaningfully present at the table?

🚩 Information: Can we effectively partner to get to the full truth if information about research options, methods, inputs, costs, benefits, and risks are not shared?

🚩 Validity: Could we be accepting partial truths as the full picture, because we are not valuing community organisations and community members as valid experts?

🚩 Ownership: Are we getting incomplete answers by valuing research processes that take from, rather than build up, community ownership?

🚩 Value: What value is generated, for whom, and at what cost?

🚩 Accountability: Are we holding funders and researchers accountable if research designs create harm or do not work?

🚩 Authorship: Whose voice is shaping the narrative and is the community fully represented?

The guidance is organised by each area and outlines the challenge, the implication, and the opportunities for community organisations, researchers, and funders.

Introduction

A guidebook for community organizations, researchers and funders to help us get from insufficient understanding to more authentic truth. In the hometown of urban research, Jonte asks aloud “why am I always being researched?” His peers are in three studies at once. A grandmother on his block, neighbors, and staff at nonprofits serving him, remember being in studies, too. Jonte is one of thousands in Chicago who, over decades, have participated in research studies with price tags in the millions, all in the name of societal change. And yet, the fruits of those studies have infrequently nourished the neighborhoods where their seeds were planted. Instead, there remains “not enough evidence” about what works, and a deep distrust between community, funder, and researcher, driven by systemic injustices: racism, segregation and disinvestment. And then, there are questions behind how evidence gets made. What if the structures we use to find what works to improve communities is negatively impacted by the same power dynamics that have propped up those systemic injustices? At its core, this is an interaction of individuals, human beings, each with their own biases. What if our research questions are unintentionally rooted in bias? Have we stopped to consider if our inputs are unfairly affecting our intended outcomes?

Read the full guidelines here.